The Cragg Vale Coiners and The Gallows Pole

The apparent tranquillity of Mytholmroyd belies a murky past involving an 18th century counterfeiting gang, the Cragg Vale Coiners. This gang’s activities were said to be so damaging that they threatened to wreck Britain’s economy!

SPOILER WARNING: this page contains details of the story of the Cragg Vale Coiners – if you’d like to watch ‘The Gallows Pole’ tv drama, or read the book, without knowing the broad details of what takes place, don’t read on….

In the mid 18th century, David Hartley learnt his trade as an ironworker in Birmingham, where the practise of clipping and forging coins was abundant. Hartley is thought to have learnt the coining process himself during his apprenticeship and later left Birmingham for fear that his illicit activities there may be discovered.

Hartley returned to his home, Bell House at Cragg Vale, in the 1760s, using his ironworking as a cover to clip or file the edges from gold coins, producing counterfeit coins from the shavings and returning the clipped coins into circulation.

Hartley seems to have been an enigmatic individual. With him as ringleader, the activity spread to other families at nearby Hill Top Farm and Keelham Farm, forming the beginnings of a gang of dozens of individuals; the Cragg Vale Coiners. Hartley became known as ‘King David’ Hartley and local publicans helped the gang by placing the counterfeit coins into circulation.

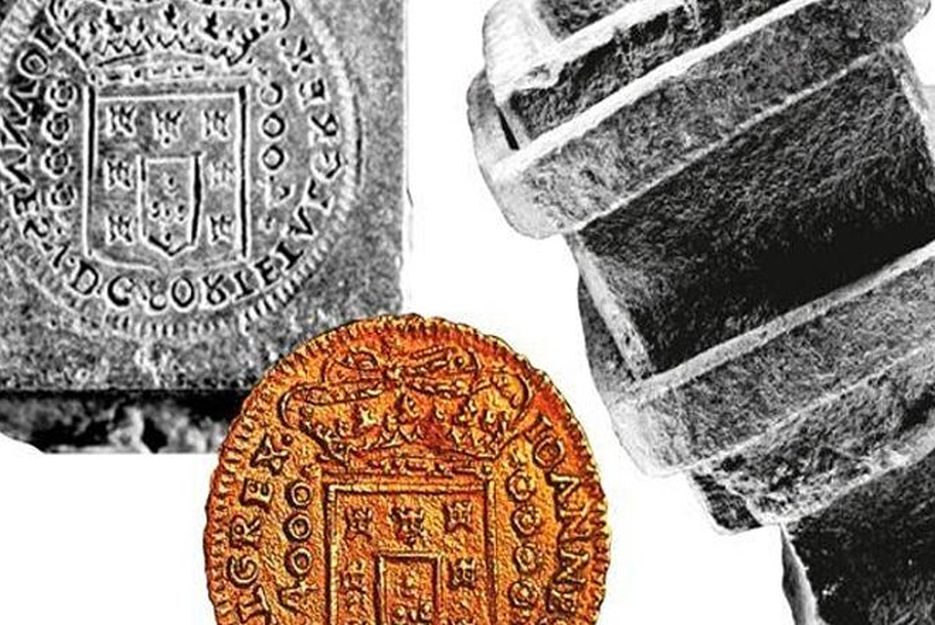

The usual method of counterfeiting used by other Coiners around the country was to produce fake coins using a cheap base metal, which was then plated or treated to give it the appearance of a gold coin. The Cragg Vale Coiners were distinct from this usual method as they collected gold fragments and forged new coins using real gold.

Gold was clipped from the edges of a coin and the coin’s milled edges recreated by rolling and beating the edge of the coin along a file. The collected gold clippings were melted down to create a blank disc, which was then stamped with an impression using dies made of spelter, a zinc alloy.

Those who were not Coiners themselves but lent the Coiners good Guineas benefitted from the activity, as the Coiners would pay a small amount to the lender of the coin in payment for the gold that was collected. The Cragg Vale Coiners would pay 22 Shillings for a full size coin (worth 21 shillings) and would then clip and shave up to forty pence worth of gold from it before returning it to circulation for its face value of 21 Shillings. The lender therefore gained a shilling as a result of the transaction whilst not actually being involved in the clipping. This helped to gain support locally and to conceal the activities of the Coiners, since nobody (except the excise collectors and the Government) suffered a loss and generally all involved made a small gain.

The Coiners would use the gold collected from about 7 or 8 genuine coins to create an imitation Portuguese Moidore, with a higher face value of 27 Shillings and feed this fake coin into circulation for its face value. They would only use about 22 Shillings worth of gold to create the fake, making a substantial profit on each new coin they forged.

**

Most of the local population were involved in the weaving trade and the region produced high quality, hardwearing Worsted cloth. After a boom during the Seven Years War (1756-1763) the woollen industry in the West Riding of Yorkshire fell into decline during the post war recession, due to a reduced demand for the Worsted which had been used largely for military uniforms.

Many of those who became involved with the Cragg Vale Coiners had trades associated with the weaving industry and were now suffering through the lack of demand for their produce. Financial pressures made the practise of clipping and forging new coins a highly attractive proposition for some.

The rugged location, primitive transport links, sparse law enforcement, and the state of the genuine coinage all created the right climate for the Coiners to flourish. The local farmhouses were surrounded by open fields or moorland, making the chances of anyone arriving unexpectedly slim and giving the Coiners ample opportunity to tidy away the evidence of their unlawful activities should anybody come to visit.

The chances of discovery were made even more remote by the fact that during the 18th century, England had no public officials corresponding to the modern day Police. Constables were unpaid and played only a minor role in law enforcement. Halifax, seven miles away, had only two Constables and two Deputy Constables and the nearest Magistrate was fourteen miles away in Bradford.

Much of the coinage in circulation at the time was old and worn, making the differentiation of a clipped or forged coin from a genuine one all the more unlikely.

**

The first reports of coining in the area were made in August 1767. A John Greenwood from Halifax had been arrested in Hamburg for coining and in his statement claimed to have learnt the practise from James Johnson, a Smith from Wadsworth.

In August 1768 the Leeds Intelligencer reported the circulation of counterfeit Guineas and in March 1769 the Leeds Mercury reported that it was thought a gang of Coiners numbering ‘half a score’ was operating in the Halifax area.

William Dighton, the Supervisor of Excise for Halifax District, had been attempting to take action against the practise of clipping for several years, with the support of Halifax attorney Robert Parker. Two Worsted Manufacturers Association inspectors, James Crabtree and William Haley, were employed to infiltrate the gang and gather evidence against the Coiners. This led to some arrests being made in September 1769, but Dighton and Parker lacked the necessary evidence to bring any of the major culprits to justice.

A breakthrough came in the following month, when James Broadbent from Mytholmroyd, who was active on the fringes of the Coiners gang, approached Dighton. Dighton allegedly offered Broadbent 100 guineas to betray ‘King David’ Hartley and his close associate, James Jagger.

On 12th October 1769 Broadbent swore a statement before magistrate Edward Rookes Leedes of Royds Hall, in the presence of Dighton, stating that he witnessed Hartley and Jagger clip four Guineas at Bell House. The statement gave Dighton and Parker the evidence they needed and two days later on the 14th of October, David Hartley was arrested at the Old Cock Inn (which is still open as a pub today) and Jagger at the Cross Pipes Inn, both in Halifax. The two were kept at York Gaol, ready for trial the following Spring.

It seems that Broadbent never received the 100 guineas he was promised. Unhappy with the situation he confided in a fellow Coiner about his lot and the two visited Isaac Hartley, David’s brother. Broadbent was somehow able to persuade the furious Isaac that he would be able to retract the statement he made to the magistrate and the plotting began to try and free David Hartley and James Jagger.

Isaac and Broadbent travelled to York and were able to confer with Hartley and Jagger whilst they exercised in the gaol’s yard. A revised statement attempting to clear Hartley and Jagger was submitted to a York attorney, but it didn’t have the desired effect – no bail was offered. Broadbent attempted to retract the statement he gave to magistrate Leedes, but this too was unsuccessful, as Leedes believed the original statement to be true.

Frustrated at every turn, Isaac Hartley met with other Coiners at an inn in Mytholmroyd, (thought to be called Barbary’s, which is now gone, but was located on the opposite side of the road to the present day Dusty Miller). It was allegedly agreed at this meeting that Dighton had to die and that a sum of 100 guineas was arranged to find the right men to carry out the nefarious deed.

Shortly after midnight on November 10th 1769 close to his home in Halifax, Dighton was approached by two men, Matthew Normanton and Robert Thomas. Dighton was shot in the head, his valuables stolen and his dead body was left showing signs of having been stamped on.

The Government was outraged. On the 14th of November the Marquis of Rockingham, Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding, was appointed to hunt down Dighton’s killers. A reward was offered for information leading to their arrest, as well as a free pardon (to anyone except the killers) who wished to turn King’s Evidence.

By late 1769 a list of nearly 80 counterfeiters had been drawn up; 30 from Cragg Vale, 20 from Sowerby, 15 from Halifax, 7 from Wadsworth and 6 from Warley and Midgley. By Christmas over 20 Coiners had been arrested, imprisoned and were awaiting trial.

The trial of David Hartley took place on 2nd April 1770, presided over by William Murray, Lord Chief Justice. Hartley was accused of clipping four guineas with James Jagger, on the evidence of James Broadbent and Joshua Stancliffe, a watchmaker from Halifax. Hartley was found guilty, sentenced to death and executed by hanging at Tynburn, near York, on April 28th.

When the trial of Dighton’s murderers took place, the case against Thomas and Normanton could not be proved because of unreliable evidence. Both men were acquitted.

In January 1774 Matthew Normanton was re-arrested, this time charged on suspicion of coining. In May, Robert Thomas confessed that he had present at Dighton’s murder, had shared the money robbed from his corpse but had not fired his pistol. In July Thomas was found guilty of highway robbery and sentenced to death – he was executed by hanging in York on 6th August and his body hung from a gibbet at Beacon Hill in Halifax.

In March 1775 Matthew Normanton failed to appear before the court and was found guilty of coining in his absence and sentenced to death. Days later, as Constables turned up at his home to arrest him, Normanton fled along the valley, but was found shortly after hiding in bushes. He was executed by hanging in York on 15th April and his body hung in its chains at Beacon Hill in Halifax, alongside that of Thomas, as a warning to others.

Despite being named in many depositions and examinations as the man that had arranged the murder of Dighton, paid the murderers and obtained and disposed of the weapons; Isaac Hartley was never charged in connection with Dighton’s murder and he died an old man (reports vary between 78 and 85 years of age) in 1815 at his home at White Lee in Mytholmroyd.

Isaac was buried in a grave alongside his brother David in the village of Heptonstall, above Hebden Bridge. David Hartley’s grave is often easily identified by a number of coins left on it by visitors to the cemetery.

It is estimated that the Cragg Vale Coiners paid £3.5m (£490m in today’s money) of fake coins into the Bank of England in the 1760s, devaluing the Pound by 9% and almost causing the British economy to collapse.

**

Bankfield Museum in Halifax has a display featuring some of the original dies used by the Coiners to stamp their gold discs into coins, as well as panels telling more of their story. Bankfield Museum has FREE entry and is open Tuesday to Saturday 10am – 4pm (closed Sundays and Mondays).

Bankfield Museum, Akroyd Park, Boothtown Road, Halifax, West Yorkshire, HX3 6HG. Tel: 01422 352334 Email: museums@calderdale.gov.uk

Heptonstall Museum Scenes for The Gallows Pole were filmed inside the Museum, which was transformed into Barbary’s, the Coiner’s watering hole. The Museum’s opening exhibition explores the lives of the Cragg Vale Coiner’s and is open to the public Thursday to Sunday 11am- 4pm Admission £3.

Heptonstall Museum, Church Yard Bottom, Heptonstall, Hebden Bridge, HX7 7PL

The 2017 novel ‘The Gallows Pole’ by Benjamin Myers tells a fictionalised account of the Coiner’s story. The Gallows Pole received a Roger Deakin award for writing concerned with “natural history, landscape and environment” and won the Walter Scott Prize 2018, the world’s biggest prize for historical fiction. Judges described the book as “a roaring furnace of a novel”.

The Gallows Pole has been adapted into a major BBC television drama by Shane Meadows, the acclaimed writer and director of hard-hitting television and film drama such as This is England and Dead Man’s Shoes. The television adaptation stars This is England actor Michael Socha as David Hartley. Other actors include This is England star Thomas Turgoose, George MacKay, who starred in the war film ‘1917’, ‘Downton Abbey’s’ Sophie McShera and Cara Theobold, and Hollyoaks star Nicole Barber-Lane.

The three-part series of The Gallows Pole began to air on BBC Two on 31st May 2023 and all episodes are available on and i player .

Sources:

Calderdale Council Museums Service

Yorkshirecoiners.com

David Glover

Huddersfield Daily Examiner